Someday at Christmas

This essay first appeared on January 1, 2017 in the Herald-Sun.

WRAL radio began playing Christmas songs around Thanksgiving. I have been singing favorites and learning new ones. One song from 1966 had never fully registered in my brain until this year. It was beautifully written by Ron Miller and made breathtaking by Stevie Wonder. A person named Lacey Sawyer created a YouTube montage for the song. Her tableau combines with the words in my mind. “Someday at Christmas there’ll be no wars, when we have learned what Christmas is for” overlays images of American soldiers climbing over rubble and making peace signs with what appear to be children in Iraq or Afghanistan. The video includes men in loud lamentation at a protest, perhaps from the Arab Spring (2011). Sawyer has pulled together photos that evoke Middle America and the Middle East, as people in Marine uniforms hand out “Toys for Tots” and two women grasp hold of a man in uniform, perhaps returning from the Middle East. Miller’s lyrics and Wonder’s voice together were originally a prayer for a world without war, where “all men are equal and no man has fear.” This prayer from 1966 intertwined voices crying out against war in Vietnam and voices calling for Civil Rights.

I have been layering this prayer with another song, from 1989, called “Fight the Power.” At the beginning of their song, Public Enemy includes these words from a 1967 speech by Civil Rights leader Thomas N. Todd: “Yet our best trained, best educated, best equipped, best prepared troops refuse to fight. Matter of fact, it’s safe to say that they would rather switch than fight.” The hope that Mr. Todd spoke of in 1967, the same year Stevie Wonder’s album debuted, was that people told to kill would refuse to do so. Playing off a cigarette ad, Todd paraphrased a prophecy from the prophet Isaiah. Todd evoked a world where troops would refuse to fight – a world where swords were switched into plowshares – and this hip-hop group brought his words to bear again in 1989. Someday at Christmas, there’ll be no wars; our best will refuse to fight.

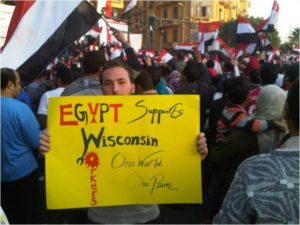

In 2011, during the “Arab Spring,” I heard a story about mothers and grandmothers in Egypt who had been teaching their sons for decades to refuse to shoot at civilians if ordered to do so. A journalist named Scott Horton spoke at a 2011 conference here in Durham about the geopolitical ramifications of U.S. sponsored torture, and he suggested that, possibly, one unpredictable result of coverage of U.S. sponsored torture of Muslim prisoners was that people in predominantly Muslim countries were galvanized to protest in the thousands against dictators who were torturing their own people – dictators like Hosni Mubarak. And, at least for a time, troops refused to fight. In a February 1, 2011 article for The National Hugh Naylor reported:

Egypt’s powerful military said yesterday it would not open fire on protesters as a coalition of Egyptian opposition groups called for a million people to take to Cairo’s streets today. ‘To the great people of Egypt, your armed forces, acknowledging the legitimate rights of the people … have not and will not use force against the Egyptian people,’ an army statement said. The concerted opposition action signaled the emergence of a unified leadership for the protests demanding the removal of the president, Hosni Mubarak.

A powerful image from Lefteris Pitarakis of the AP shows an Egyptian woman kissing an officer who could be her grandson. The NBC news ran these words: “An Egyptian anti-government activist kisses a riot police officer following clashes in Cairo, Egypt, Friday, Jan. 28, 2011.” Something akin happened in Wisconsin that same winter, as police officers joined hands with protestors against Governor Scott Walker.

Here is some news you may not have seen widely shared. Joshua Berlinger of CNN reported in July, 2016: “Many of the protests against police violence have been peaceful. In Dallas – before a gunman killed five police officers at a Black Lives Matter rally . . . officers were even posing for photos with demonstrators.” Which brings me to an image that could beautifully accompany Stevie Wonder’s voice. Ieshia Evans was protesting police violence – specifically the Baton Rouge police department, when a photographer named Jonathan Bachman caught her lamentation. She walks forward, hands out, as police officers in full riot gear appear to back away. The image has gone viral, as a visual prayer for otherwise. It is an image of disarming, non-violent courage, remarkable to people in part because she is a visually beautiful woman and the police officers look as if they would prefer to switch, rather than fight. It is not the only image of hope. There are others. I pray we see more. “Maybe not in time for you and me, but someday at Christmastime.”